Vivianite: Chromism

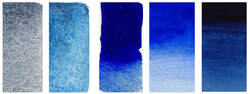

Figure 1. a. vivianite, b. azurite, c. synthetic ultramarine, d.cobalt, e. Prussian blue

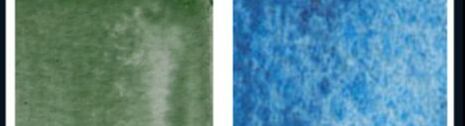

Figure 2. Celadonite and Azurite

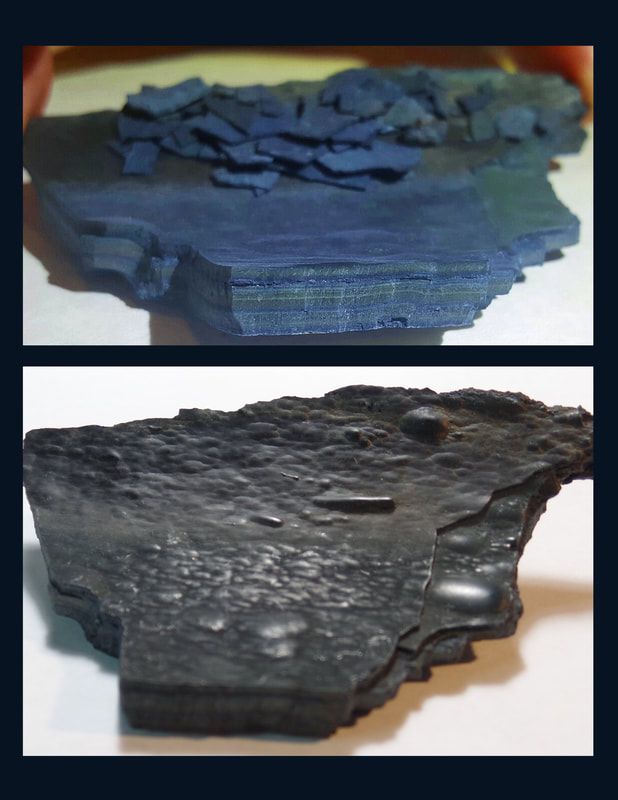

Figure 3. Top image is a piece of vivianite from waster-water pipes soon after removal. Bottom image is the same piece of vivianite a year later.

Figure 4 A. Bentwood cedar chest with vivianite by Albert Edward Edenshaw. B. Bentwood cedar chest on which vivianite has turned black, by same carver. moa.ubc.ca

|

Chromism

On NW Coast Native artifacts the presence of vivianite can be determined to a high degree of certainty through visual examination if you know some of the characteristics that distinguish it from other blue and green pigments. The blue of vivianite is distinctive from other blue pigments and is easily spotted, especially in side-by-side comparison to other blues. (FIG 1) However, vivianite has an extensive range of shades that can make it difficult to identify as can be seen in the image at the top of the page. Some shades of vivianite stray well into the green shades, particularly as it undergoes chromism. This has led to many people misidentifying it as celadonite or a copper oxide. (FIG 2) When visually identifying vivianite remember it is not as reflective as other pigments (even with a lipid binder vivianite is not reflective; it is the binder reflecting light) but rather vivianite absorbs light. In comparison with the “brighter” azurite, Prussian and ultramarine blues, vivianite is a more muted color and is often described as “earthy” and “soft”. Vivianite tends to have a very clean blue mass tone with no undertone. It sometimes has a green or gray undertone, though. The tinting strength of vivianite is low, so, unless the paint has a high ratio of pigment to vehicle, or applied in heavy, or multiple coats, it is rarely consistently opaque, allowing the substrate to be visible. Recognizing the characteristics of vivianite, its unique coloration, how it looks when applied with water versus fat-based binders, knowing the range of shades and what the finish should look like all contribute to being able to discern the presence of vivianite on artifacts as opposed to other pigments. Knowing the relative age of the piece, or at least when it became part of a collection is also helpful in identifying the pigment. Chromism in Process On NWC objects the darkening of vivianite helps to immediately identify the pigment. The tertiary fields of the chest in FIG 4B show vivianite that has darkened. In the image the paint in the tertiary fields looks like a soft black, has a different texture and is not as dark or reflective as the formline which is painted black. This reflectivity and different texture are notable when determining darkened vivianite from regular black paint. While black and red were often mixed with a lipid binder that causes the paint to have a reflective sheen, on those same pieces vivianite was usually applied with just water. Some people argue that those tertiary fields were deliberately painted with black or dark brown. However, since formline design has discreet fields of color that are proscribed by tradition, it is unlikely artists used black paint in tertiary fields, especially when black is already present in another field. Because no other pigment changes color the way vivianite does, there is little doubt of what the pigment is. There are many factors which may contribute to vivianite’s chromism: the type of binder, exposure to light, preservation treatments, and other, as-yet unknown factors could all probable reasons for the color change. The typical species of woods used, red and yellow cedar, for bentwood boxes and chests, contain natural oils. These oils may be part of the cause of vivianite changing color on some objects. In the process of restoring and repairing NW Coast objects I have frequently observed the alteration of paint colors, even with modern acrylic paints, due to the natural wood oils. On some objects the random color alteration of vivianite may be attributed to these oils. However, why the paint has darkened on hundreds of objects but not on many others needs further, in depth study. The people of NW Coast cultures produced a wealth of wooden objects, of which bentwood chests are some of the finest examples of their carving and painting skills. A great number of these chests were painted with vivianite in the tertiary fields; unfortunately, it is all too common to find areas of chests, and even entire chests on which vivianite paint has changed color. My study of bentwood chests painted with blue includes twenty-five years of studying three chests at the University of British Columbia Museum of Anthropology attributed to Albert Edward Edenshaw. The blue paint on the chest in FIG 4A can clearly be seen in the tertiary fields, however, during the study period the vivianite paint has darkened measurably (these photographs of both figures 4 A & B were taken more than ten years ago). The tertiary fields on the chest in figure 4A have darkened since I first began studying this chest. An in-depth study of the objects made by Albert Edward Edenshaw indicates he did not use lipid binders with vivianite; he used vivianite frequently and had to be familiar with vivianite darkening when applied with a lipid binder. It is likely that this chest was treated post hoc, with waxes or oils in an effort to preserve the wood. Unfortunately, this is disastrous for maintaining the true color of vivianite. The three Edenshaw chests are on exhibit with many other artifacts in a large glass room that allows constant exposure to UV light. While any light is deleterious to vivianite, it is well known that UV light is directly responsible, for not only chromism, but also, the overall deterioration of paint and wood. The persistent exposure to UV light is a major concern in the long-term preservation of these chests as well as all the other objects in this space. The color changes to vivianite paint will eventually cause an irreparable loss of information and reference material (including the objects themselves) for current and future generations. |