Celadonite and Vivianite: Blue and Green on the NW Coast

Two mysteries persisted for many years in the field of NW Coast Native art regarding the pigments on NW Coast Native objects: what was used to make green and blue paint? The common consensus has been both green and blue pigments were copper carbonates. However, a study done by the Canadian Conservation Institute in 1990 determined celadonite is the green mineral pigment most commonly found on northern NW Coast Native artifacts but there was no analysis of blue pigments by the CCI. In 2010 I identified a sample of the blue pigment through SEM/EDX in 2010 as an iron phosphate called vivianite.

There is no question the northern tribes (Haida, Tlingit, etc.) have long used a green pigment, but the use of it by Coast Salish peoples is almost entirely unknown. In 1984 Dr. Roy Carlson, Professor Emeritus of archeology from Simon Fraser University, removed a pigment grinding stone (Fig 1) from the 3500-4000 year level of a Straits Salish midden on Pender Island, located in the Gulf of Georgia, British Columbia. One surface of this stone is partially covered in green pigment which I have identified through SEM/EDX and XRF as celadonite, more commonly known as green earth, or terra verte. This grinding stone establishes a tentative timeline for and confirms the use of this pigment by the Coast Salish.

In queries to a wide variety of people who include Coast Salish elders and artists, scholars, anthropologists, archeologists and people who have worked with Coast Salish art in different capacities, it was so rare as to be nonexistent to find someone who could remember seeing celadonite on Coast Salish pieces; I did not accept this as the final answer, however. I already knew the Burke Museum holds two Coast Salish spindle whorls with celadonite paint on them and this prompted me to begin an exhaustive search through numerous museum collections and the literature until I found more pieces.

This spindle whorl (Fig 2) is an excellent example of how pigments behave when mixed with animal fats. Originally the surface was painted with celadonite and red ochre with a water medium. The surface has been saturated with lanolin from spinning wool, which has caused the colors to darken and take on a satin finish but small areas of the original pale green color and matte finish can be seen inside some of the spokes where the lanolin was not able to reach.

The Blue Pigment

While my questions about the green pigment were answered by the CCI’s report, I was not as fortunate with blue pigment. And if I thought the green pigment was overlooked, the blue was almost completely invisible to the point I was told by far too many people, “What blue?” and “Blue was not used until after contact.” This statement belied the fact I had examined a Tlingit shaman’s apron estimated at 400 years old as well as innumerable masks, rattles, etc., all of which were certainly pre-contact, which bore blue pigment. The book, “North American Indian Art”, by Paul Hamlyn has photographs of the earliest collection of Tlingit artifacts in the world held by the Kunstkamera (formerly Peter the Great Museum of Anthropology and Ethnography), Leningrad, Russia. The majority of the collection pictured in this book is pre-1860’s and all of it is pre-1880’s and a significant number of pieces bear blue paint clearly demonstrating blue paint was not a post-contact phenomena. What had begun as a simple curiosity and desire to use traditional materials was whetted by these artifacts, and I began researching the blue pigment in earnest.

In 2010 I obtained a small amount of blue pigment which I analyzed using scanning electron microscopy. It was vivianite, an iron phosphate mineral (Fe2+Fe2+2(PO4)2·8H2O), commonly found anywhere iron is present along with decomposing organic matter and an anaerobic environment: basically the bottom of every body of water, bog and swamp. It is a forming mineral, meaning it is constantly in the process of forming from basic elements into an earthy, clay, stone or crystalline form. Because vivianite is a forming mineral, some deposits of are millions of years old while others are just now forming, along with everything in between.

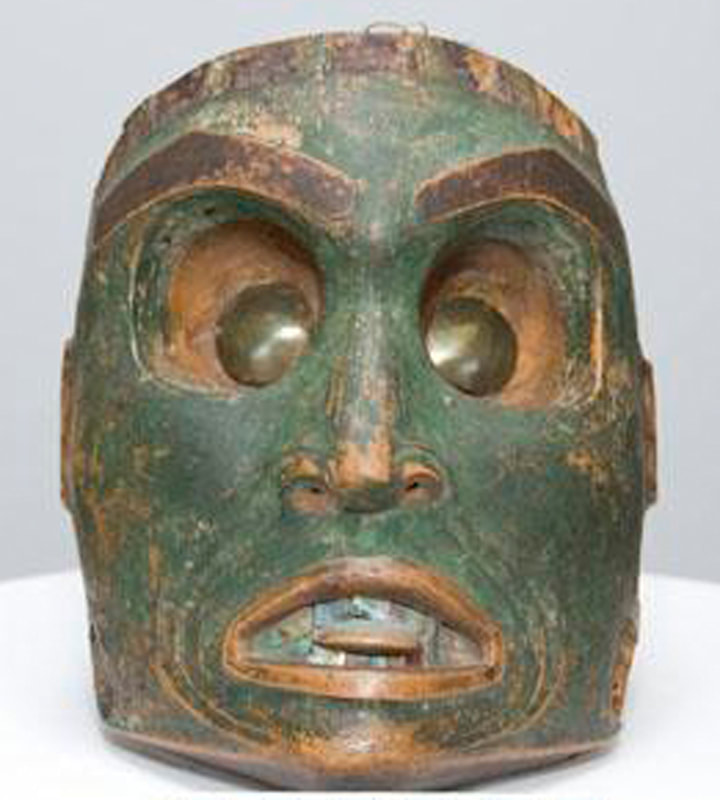

Vivianite is a simple mineral compound that displays complex behaviors with light and oxidation both playing critical roles in color changes. Upon presentation it appears as a white clay but rapidly undergoes a photochemical process from being exposed to light which causes it to change color to blue. Experiments I have conducted show that this color change can occur in less than an 15 minutes in bright sunlight, more slowly with less light. It also begins an oxidation process similar to that which occurs with other mineral oxides which affects the color. When seen on NW Coast artifacts these color changes are quite evident (Fig 3) but all the factors for color change are not yet known. In my own experiments specific types of binders cause deepening of chromas and color changes. In Europe where vivianite has only recently been found on pieces dating as far back as the 11th century, they are ardently seeking explanations for color changes on artworks by Rembrandt, Vermeer, Du Cuyp and others. The areas painted with vivianite have partially changed from blue to an olive green, brown, gray and black. There is speculation this may be due to exposure to toxic elements such as mercury and arsenic and/or to preservation and conservation treatments formerly practiced by museums and collectors.

Matters are made more complicated by vivianite ranging from pale, almost sky blue (Fig 4) to deeply saturated dark blue (Fig 5), greenish blue and gray blue. It is well documented by mineralogists that vivianite crystals change color, and common knowledge about vivianite clay is replete with anecdotes about how it can present as gray or white only to change color with exposure to sunlight.

The composition of NW Coast designs and the strict rules pertaining to color use insure color changes of vivianite are immediately apparent: any area which would normally be left unpainted or would have been painted blue, which is now darkened to black, as in figure 3, is a red flag. Whether the color change is a result of something the original artist did, or whether it is a result of storage conditions, treatments or factors we have not yet determined, to be able to properly store and conserve these objects requires our identification of vivianite on artifacts and understanding the behaviors and characteristics of this mineral pigment.

Establishing the use of both celadonite and vivianite by NW Coast Native artists using the technology available for analysis and for mapping deposits has opened the doors to determining more closely where particular artifacts originated, matching sibling pieces or objects from the same area, and in some cases the potential for dating pieces more closely is possible. The research into vivianite using microscopy technologies has added a new level of scholarship to the field of NW Coast Native art which is lending validity to the entire field of NW Coast Native art and culture that has been slow in coming.

The study of pigments and paint technology can help inform us of the complex conceptual ability of a people to utilize their environment and resources beyond sustenance to enhance both their sacred and profane lives. It gives us insights into the material cultures of the NW Coast and the technological and behavioral evolution and practices including a basic knowledge of chemistry and mineralogy. In a far more encompassing aspect this study helps us see an overarching manifestation of dedication to the creative and spiritual complexities of their cosmos.

There is no question the northern tribes (Haida, Tlingit, etc.) have long used a green pigment, but the use of it by Coast Salish peoples is almost entirely unknown. In 1984 Dr. Roy Carlson, Professor Emeritus of archeology from Simon Fraser University, removed a pigment grinding stone (Fig 1) from the 3500-4000 year level of a Straits Salish midden on Pender Island, located in the Gulf of Georgia, British Columbia. One surface of this stone is partially covered in green pigment which I have identified through SEM/EDX and XRF as celadonite, more commonly known as green earth, or terra verte. This grinding stone establishes a tentative timeline for and confirms the use of this pigment by the Coast Salish.

In queries to a wide variety of people who include Coast Salish elders and artists, scholars, anthropologists, archeologists and people who have worked with Coast Salish art in different capacities, it was so rare as to be nonexistent to find someone who could remember seeing celadonite on Coast Salish pieces; I did not accept this as the final answer, however. I already knew the Burke Museum holds two Coast Salish spindle whorls with celadonite paint on them and this prompted me to begin an exhaustive search through numerous museum collections and the literature until I found more pieces.

This spindle whorl (Fig 2) is an excellent example of how pigments behave when mixed with animal fats. Originally the surface was painted with celadonite and red ochre with a water medium. The surface has been saturated with lanolin from spinning wool, which has caused the colors to darken and take on a satin finish but small areas of the original pale green color and matte finish can be seen inside some of the spokes where the lanolin was not able to reach.

The Blue Pigment

While my questions about the green pigment were answered by the CCI’s report, I was not as fortunate with blue pigment. And if I thought the green pigment was overlooked, the blue was almost completely invisible to the point I was told by far too many people, “What blue?” and “Blue was not used until after contact.” This statement belied the fact I had examined a Tlingit shaman’s apron estimated at 400 years old as well as innumerable masks, rattles, etc., all of which were certainly pre-contact, which bore blue pigment. The book, “North American Indian Art”, by Paul Hamlyn has photographs of the earliest collection of Tlingit artifacts in the world held by the Kunstkamera (formerly Peter the Great Museum of Anthropology and Ethnography), Leningrad, Russia. The majority of the collection pictured in this book is pre-1860’s and all of it is pre-1880’s and a significant number of pieces bear blue paint clearly demonstrating blue paint was not a post-contact phenomena. What had begun as a simple curiosity and desire to use traditional materials was whetted by these artifacts, and I began researching the blue pigment in earnest.

In 2010 I obtained a small amount of blue pigment which I analyzed using scanning electron microscopy. It was vivianite, an iron phosphate mineral (Fe2+Fe2+2(PO4)2·8H2O), commonly found anywhere iron is present along with decomposing organic matter and an anaerobic environment: basically the bottom of every body of water, bog and swamp. It is a forming mineral, meaning it is constantly in the process of forming from basic elements into an earthy, clay, stone or crystalline form. Because vivianite is a forming mineral, some deposits of are millions of years old while others are just now forming, along with everything in between.

Vivianite is a simple mineral compound that displays complex behaviors with light and oxidation both playing critical roles in color changes. Upon presentation it appears as a white clay but rapidly undergoes a photochemical process from being exposed to light which causes it to change color to blue. Experiments I have conducted show that this color change can occur in less than an 15 minutes in bright sunlight, more slowly with less light. It also begins an oxidation process similar to that which occurs with other mineral oxides which affects the color. When seen on NW Coast artifacts these color changes are quite evident (Fig 3) but all the factors for color change are not yet known. In my own experiments specific types of binders cause deepening of chromas and color changes. In Europe where vivianite has only recently been found on pieces dating as far back as the 11th century, they are ardently seeking explanations for color changes on artworks by Rembrandt, Vermeer, Du Cuyp and others. The areas painted with vivianite have partially changed from blue to an olive green, brown, gray and black. There is speculation this may be due to exposure to toxic elements such as mercury and arsenic and/or to preservation and conservation treatments formerly practiced by museums and collectors.

Matters are made more complicated by vivianite ranging from pale, almost sky blue (Fig 4) to deeply saturated dark blue (Fig 5), greenish blue and gray blue. It is well documented by mineralogists that vivianite crystals change color, and common knowledge about vivianite clay is replete with anecdotes about how it can present as gray or white only to change color with exposure to sunlight.

The composition of NW Coast designs and the strict rules pertaining to color use insure color changes of vivianite are immediately apparent: any area which would normally be left unpainted or would have been painted blue, which is now darkened to black, as in figure 3, is a red flag. Whether the color change is a result of something the original artist did, or whether it is a result of storage conditions, treatments or factors we have not yet determined, to be able to properly store and conserve these objects requires our identification of vivianite on artifacts and understanding the behaviors and characteristics of this mineral pigment.

Establishing the use of both celadonite and vivianite by NW Coast Native artists using the technology available for analysis and for mapping deposits has opened the doors to determining more closely where particular artifacts originated, matching sibling pieces or objects from the same area, and in some cases the potential for dating pieces more closely is possible. The research into vivianite using microscopy technologies has added a new level of scholarship to the field of NW Coast Native art which is lending validity to the entire field of NW Coast Native art and culture that has been slow in coming.

The study of pigments and paint technology can help inform us of the complex conceptual ability of a people to utilize their environment and resources beyond sustenance to enhance both their sacred and profane lives. It gives us insights into the material cultures of the NW Coast and the technological and behavioral evolution and practices including a basic knowledge of chemistry and mineralogy. In a far more encompassing aspect this study helps us see an overarching manifestation of dedication to the creative and spiritual complexities of their cosmos.