|

L: Miniature dish for grinding pigment. Note the curved lip inside to keep the pigment from escaping. Burke Museum, Seattle Wa

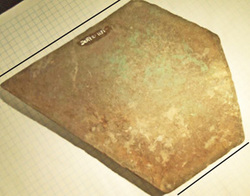

R: Grinding stone for red ochre found in the 35-4000 level of Coast Salish midden on Pender Is. BC. Most of the surface of this stone is worn smooth from use. Simon Fraser University, Surrey, BC |